Our Lutheran Community Good Friday service for this year was themed: “Witness to the Crucifixion”. As the story was read, we heard from Judas, Pilate’s wife, Barrabas, Mary (Jesus’ mother), the Roman centurion, and Mary Magdalene. It was unbelievably powerful stuff to hear the words of the characters pour forth with emotion: anger, grief, glee, resentment, curiosity, expectation, loss.

I spoke as Mary Magdalene and I was the last witness, lingering at the tomb. It’s been an emotional week, but in those moments when I was thinking as the Magdalen- I thought of having such deep love for Jesus and knowing nothing of resurrection, of believing all on which I had built my hopes was gone. I was devastated and the following words are what I spoke, through tears and some sobs. At one point, I tore my wrap- rending my garments- until I laid down in the dried palms from Palm Sunday- slain in grief. Ah, Mary Magdalene- a hero to me on Good Friday and in the days to come…

I am the last one at the tomb. I cannot leave. There are two Roman guards, but they don’t see me. They could- I’m not hiding. But they don’t want to.

The other disciples have left. The other women have left. Only me- hovering around, unseen and unacknowledged. There are the visible disciples- Peter, Judas, Andrew, James, and John. And then there are the invisible disciples… the ones the visible disciples and others tried not to see.

Do you know what it’s like to feel invisible? To know that you are in a crowd of people who do not know you and, therefore, do not see you. Worse can you imagine the feeling of forced invisibility? When you know people can see you, know who you are, but choose to ignore you… choose to “not” see you… decide that you do not merit acknowledgement… you are invisible.

And if you are invisible to people, you may as well be invisible to God. This is how I felt, constantly, before Jesus… before he cast out the demons that plagued me. When that pain and torment fled, I felt my body re-appear. My eyes came back… because Jesus met them and then so did other people. My hands came back… because Jesus would pass food to me and take food from me… and then so did other people. My feet came back… reappeared because I could walk next to someone, with the others who followed Jesus. My voice made noise again… words that were heard, received, responded to… by Jesus and by others. My face came back- as it was touched and kissed by Jesus.

Slowly my body reappeared and I was no longer missing, no longer unseen. I was made visible by Love, by living words of hope… I was made visible by Jesus and when Jesus saw you, everyone around him saw you. More, though, and this is the part that’s hard to explain… when Jesus saw you, it felt like God saw you. Saw right through you and not only were you visible, but you were bare and exposed, not naked… just visible and… known…

Now… now… Now the eyes that saw me, saw everything are closed. The hands that touched and cradled and fed are pierced and still. The feet that led and walked beside and nudged… the feet are still. They stopped bleeding before we got to the tomb. The mouth, the mouth that poured forth words of love… words like no other… words of welcome… of hope… of God with us right now… that mouth is silent. Silent! The warm lips that offered a kiss of peace are cold and still. His mouth! Rabbouni!

(Clothing torn here)

How can the world exist without him? How can this be the same place that beheld and held that body?

Who will see me? Who will see us?

Who will speak of hope and of God’s love?

Who will feed the people that no one sees?

Who will heal?

Who will stay awake in the night with those who cannot sleep?

How can we live without Jesus, without his body among us? How can we go on without him? How will I live without the One that made me visible? Does my body exist without the Body that made me whole?

I cannot leave this tomb. How can I abandon his body? As long as I stay here, at this tomb, he is not alone. If I stay, he is still visible, even behind the stone. I know he’s there. If I stay, Jesus’ body is still real. And as long as his body is real, so is mine.

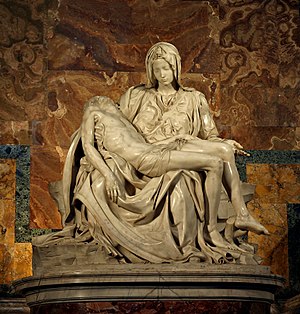

The second image is the Pietà, Michaelangelo’s to be specific. I keep thinking of this image in connection with the violent deaths of the children of Sandy Hook, Connecticut. It is likely that most of those parents were not able to cradle the bodies of their babies- stopped from doing so because of the cause of death and the condition of the bodies. Thus, I think of that image of Mary cradling the grown Jesus and remembering in her mind how she held him so many times before. I know those parents are remembering every moment they held their children. The other thoughts that are probably running through their minds are too hard for me to imagine. Not impossible to imagine, but too hard for me to consider and still let go of my own toddler and refuse to live in fear.

The second image is the Pietà, Michaelangelo’s to be specific. I keep thinking of this image in connection with the violent deaths of the children of Sandy Hook, Connecticut. It is likely that most of those parents were not able to cradle the bodies of their babies- stopped from doing so because of the cause of death and the condition of the bodies. Thus, I think of that image of Mary cradling the grown Jesus and remembering in her mind how she held him so many times before. I know those parents are remembering every moment they held their children. The other thoughts that are probably running through their minds are too hard for me to imagine. Not impossible to imagine, but too hard for me to consider and still let go of my own toddler and refuse to live in fear.